Publication

Reading Time

Introducing Flama 1.7: Support for Domain-Driven Design

You've probably already heard about the recent release of Flama 1.7, which brought some exciting new features to help you with the development and productionalisation of your ML APIs. This post is precisely devoted to one of the main highlights of that release: Support for Domain-Driven Design. But, before we dive into the details with a hands-on example, we recommend you to bear in mind the following resources (and, get familiar with them if you haven't already):

- Official Flama documentation: Flama documentation

- Post introducing Flama for ML APIs: Introduction to Flama for Robust Machine Learning APIs

Now, let's get started with the new feature and see how you can leverage it to build robust and maintainable ML APIs.

Table of contents

This post is structured as follows:

What is Domain-Driven Design?

Brief Overview

In modern software development, aligning business logic with the technical design of an application is essential. This is where Domain-Driven Design (DDD) shines. DDD emphasizes building software that reflects the core domain of the business, breaking down complex problems by organizing code around business concepts. By doing so, DDD helps developers to create maintainable, scalable, and robust applications. In what follows we introduce what we consider the most important concepts of DDD that you should be aware of. Before we dive into them, let's remark that this post is not intended to be a comprehensive guide to DDD, nor a substitute of the main references on the topic. Indeed, we recommend the following resources to get a deeper understanding of DDD:

- Cosmic Python by Harry Percival and Bob Gregory: This book is a great resource to learn how to apply DDD in Python.

- Domain-Driven Design: Tackling Complexity in the Heart of Software by Eric Evans: This is the book that introduced DDD to the world, and it's a must-read for anyone interested in developing a deep understanding of DDD.

Key Concepts

Before diving deeper into any of the key concepts of DDD, we recommend you to have a look at a quite useful figure by Cosmic Python where these are shown in the context of an app, thus showing how they're interconnected: figure.

Domain Model

The concept of domain model can be explained by a simplistic definition of its terms:

- domain refers to the specific subject area of activity (or knowledge) that our software is being built to support for.

- model refers to a simple representation (or abstraction) of the system or process that we are trying to encode in our software.

Thus, the domain model is a fancy (but standard and useful) way to refer to the set of concepts and rules that business owners have in their mind about how the business works. This is what we also, and commonly, refer to as the business logic of the application, including the rules, constraints, and relationships that govern the behavior of the system.

We'll refer to the domain model as the model from now on.

Repository pattern

The repository pattern is a design pattern that allows for the decoupling the model from the data access. The main idea behind the repository pattern is to create an abstraction layer between the data access logic and the business logic of an application. This abstraction layer allows for the separation of concerns, making the code more maintainable and testable.

When implementing the repository pattern, we typically define an interface that specifies the standard methods that any

other repository must implement (AbstractRepository). And, then, a particular repository is defined with the concrete

implementation of these methods where the data access logic is implemented (e.g., SQLAlchemyRepository). This design

pattern aims at isolating the data manipulation methods so that they can be used seamlessly elsewhere in the

application, e.g. in our domain model.

Unit of work pattern

The unit of work pattern is the missing part to finally decouple the model from the data access. The unit of work encapsulates the data access logic and provides a way to group all the operations that must be performed on the data source within a single transaction. This pattern ensures that all the operations are performed atomically.

When implementing the unit of work pattern, we typically define an interface that specifies the standard methods that

any other unit of work must implement (AbstractUnitOfWork). And, then, a particular unit of work is defined with the

concrete implementation of these methods where the data access logic is implemented (e.g., SQLAlchemyUnitOfWork). This

design allows for a systematic handling of the connection to the data source, without the need to change the

implementation of the business logic of the application.

Implementing DDD with Flama

After the quick introduction to the main concepts of DDD, we're ready to dive into the implementation of DDD with Flama. In this section, we'll guide you through the process of setting up the development environment, building a base application, and implementing DDD concepts with Flama.

Before proceeding with the example, please have a look at Flama's naming convention regarding the main DDD concepts we've just reviewed:

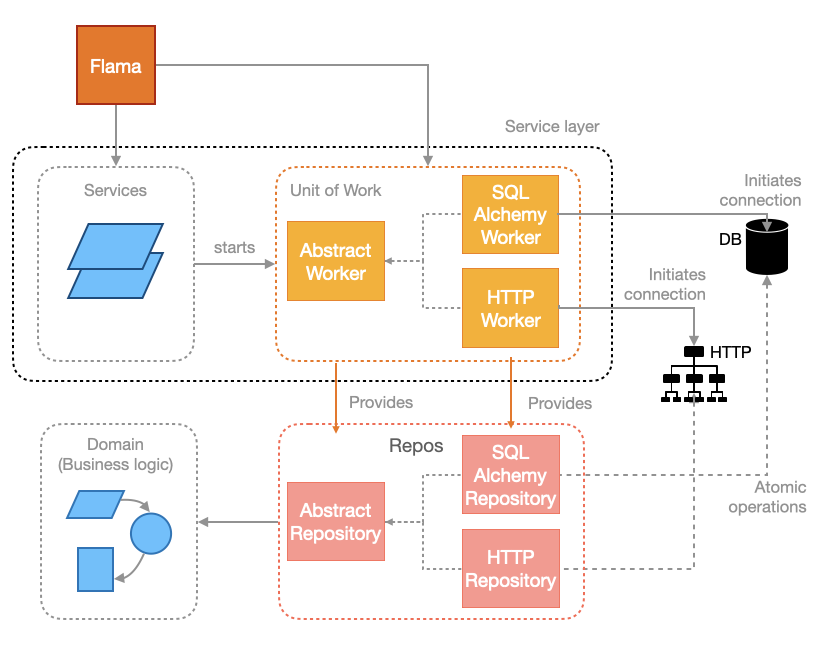

As you can see in the figure above, the naming convention is quite intuitive: Repository refers to the repository

pattern; and, Worker refers to the unit of work. Now, we can now move on to the implementation of a Flama API which

uses DDD. But, before we start, if you need to review the basics on how to create a simple API with flama, or how to

run the API once you've already the code ready, then you might want to check out the

quick start guide. There, you'll find the fundamental concepts and

steps required to follow this post. Now, without further ado, let's get started with the implementation.

Setting up the development environment

Our first step is to create our development environment, and install all required dependencies for this project. The

good thing is that for this example we only need to install flama to have all the necessary tools to implement JWT

authentication. We'll be using poetry to manage our dependencies, but you can also use

pip if you prefer:

poetry add "flama[full]" "aiosqlite"The aiosqlite package is required to use SQLite with SQLAlchemy, which is the database we'll be using in this example.

If you want to know how we typically organise our projects, have a look at our previous post

here, where we

explain in detail how to set up a python project with poetry, and the project folder structure we usually follow.

Base application

Let's start with a simple application that has a single public endpoint. This endpoint will return a brief description of the API.

# src/app.pyfrom flama import Flama

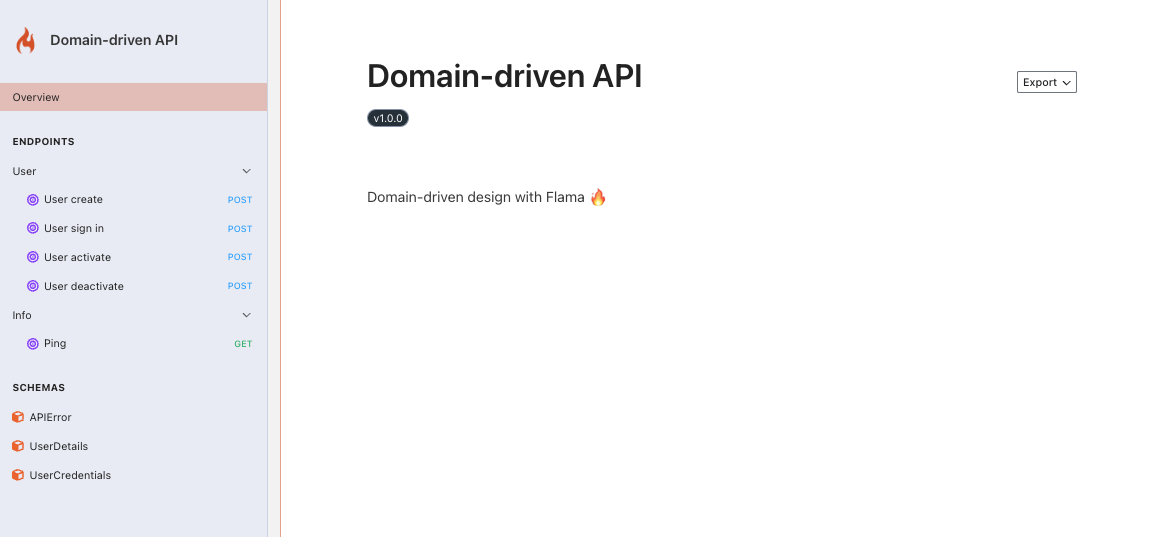

app = Flama( title="Domain-driven API", version="1.0.0", description="Domain-driven design with Flama 🔥", docs="/docs/",)

@app.get("/", name="info")def info(): """ tags: - Info summary: Ping description: Returns a brief description of the API responses: 200: description: Successful ping. """ return {"title": app.schema.title, "description": app.schema.description, "public": True}If you want to run this application, you can save the code above in a file called app.py under the src folder, and

then run the following command (remember to have the poetry environment activated, otherwise you'll need to prefix the

command with poetry run):

flama run --server-reload src.app:app

INFO: Started server process [3267]INFO: Waiting for application startup.INFO: Application startup complete.INFO: Uvicorn running on http://127.0.0.1:8000 (Press CTRL+C to quit)where the --server-reload flag is optional and is used to reload the server automatically when the code changes. This

is very useful during development, but you can remove it if you don't need it. For a full list of the available options,

you can run flama run --help, or check the documentation.

Alternatively, you can also run the application by running the following script, which you can save as __main__.py

under the src folder:

# src/__main__.pyimport flama

def main(): flama.run( flama_app="src.app:app", server_host="0.0.0.0", server_port=8000, server_reload=True )

if __name__ == "__main__": main()And then, you can run the application by executing the following command:

poetry run python src/__main__.py

INFO: Started server process [3267]INFO: Waiting for application startup.INFO: Application startup complete.INFO: Uvicorn running on http://127.0.0.1:8000 (Press CTRL+C to quit)DDD in action

Now, having set up a minimal skeleton for our application, we can start implementing the DDD concepts we've just reviewed within the context of a simple example which tries to mimic a real-world scenario. Let's assume we are requested to develop an API to manage users, and we are provided with the following requirements:

- We want to create new users via a

POSTrequest to/user/, providing the user's name, surname, email, and password. - Any user created will be stored in a database with the following schema:

id: unique identifier for the user.name: user's name.surname: user's surname.email: user's email.password: user's password. This should be hashed before storing it in the database.active: a boolean flag to indicate whether the user is active or not. By default, users are created as inactive.

- Users created must activate their account by sending a

POSTrequest to/user/activate/with their email and password. Once the user is activated, the user's status must be updated in the database to active. - Users can sign in by sending a

POSTrequest to/user/signin/with their email and password. If the user is active, the API must return all user's information. Otherwise, the API must return an error message. - Users that want to deactivate their account can do so by sending a

POSTrequest to/user/deactivate/with their email and password. Once the user is deactivated, the user's status must be updated in the database to inactive.

This set of requirements constitute what we've previously referred to as the domain model of our application, which essentially is nothing but a materialisation of the following user workflow:

- A user is created via a

POSTrequest to/user/. - The user activates their account via a

POSTrequest to/user/activate/. - The user signs in via a

POSTrequest to/user/signin/. - The user deactivates their account via a

POSTrequest to/user/deactivate/. - The user can repeat steps 2-4 as many times as they want.

Now, let's implement the domain model using the repository and worker patterns. We'll start by defining the data model, and then we'll implement the repository and worker patterns.

Data model

Our users data will be stored in a SQLite database (you can use any other database supported by SQLAlchemy). We'll use

the following data model to represent the users (you can save this code in a file called models.py under the src

folder):

# src/models.pyimport uuid

import sqlalchemyfrom flama.sqlalchemy import metadatafrom sqlalchemy.dialects.postgresql import UUID

__all__ = ["user_table", "metadata"]

user_table = sqlalchemy.Table( "user", metadata, sqlalchemy.Column("id", UUID(as_uuid=True), primary_key=True, nullable=False, default=uuid.uuid4), sqlalchemy.Column("name", sqlalchemy.String, nullable=False), sqlalchemy.Column("surname", sqlalchemy.String, nullable=False), sqlalchemy.Column("email", sqlalchemy.String, nullable=False, unique=True), sqlalchemy.Column("password", sqlalchemy.String, nullable=False), sqlalchemy.Column("active", sqlalchemy.Boolean, nullable=False),)Besides the data model, we need a migration script to create the database and the table. For this, we can save the

following code in a file called migrations.py at the root of the project:

# migrations.pyfrom sqlalchemy import create_engine

from src.models import metadata

if __name__ == "__main__": # Set up the SQLite database engine = create_engine("sqlite:///models.db", echo=False)

# Create the database tables metadata.create_all(engine)

# Print a success message print("Database and User table created successfully.")And then, we can run the migration script by executing the following command:

> poetry run python migrations.py

Database and User table created successfully.Repository

In this example we are going to need only one repository, namely the repository which will handle the atomic operations

on the user table, the name of which will be UserRepository. Thankfully, flama provides a base class for

repositories related to SQLAlchemy tables, called SQLAlchemyTableRepository.

The class SQLAlchemyTableRepository provides a set of methods to perform CRUD operations on the table, specifically:

create: Creates new elements in the table. If the element already exists, it will raise an exception (IntegrityError), otherwise it will return the primary key of the new element.retrieve: Retrieves an element from the table. If the element does not exist, it will raise an exception (NotFoundError), otherwise it will return the element. If more than one element is found, it will raise an exception (MultipleRecordsError).update: Updates an element in the table. If the element does not exist, it will raise an exception (NotFoundError), otherwise it will return the updated element.delete: Deletes an element from the table.list: Lists all the elements in the table that match the clauses and filters passed. If no clauses or filters are given, it returns all the elements in the table. If no elements are found, it returns an empty list.drop: Drops the table from the database.

For the purposes of our example, we don't need any further action on the table, so the methods provided by the

SQLAlchemyTableRepository are sufficient. We can save the following code in a file called repositories.py under the

src folder:

# src/repositories.pyfrom flama.ddd import SQLAlchemyTableRepository

from src import models

__all__ = ["UserRepository"]

class UserRepository(SQLAlchemyTableRepository): _table = models.user_tableAs you can see, the UserRepository class is a subclass of SQLAlchemyTableRepository, and it only requires the table

to be set in the _table attribute. This is the only thing we need to do to have a fully functional repository for the

user table.

If we wanted to add custom methods beyond the standard CRUD operations, we could do so by defining them in the

UserRepository class. For example, if we wanted to add a method to count the number of active users, we could do so as

follows:

# src/repositories.pyfrom flama.ddd import SQLAlchemyTableRepository

from src import models

__all__ = ["UserRepository"]

class UserRepository(SQLAlchemyTableRepository): _table = models.user_table

async def count_active_users(self): return len((await self._connection.execute(self._table.select().where(self._table.c.active == True))).all())Although we won't be using this method in our example, it's good to know that we can add custom methods to the repository if needed, and how they are implemented in the context of the repository pattern. This is a powerful design pattern as we can already see, since we can implement here all the data access logic without having to change the business logic of the application (which is implemented in the corresponding resource methods).

Worker

The unit-of-work pattern is used to encapsulate the data access logic and provide a way to group all the operations that

must be performed on the data source within a single transaction. In flama the UoW pattern is implemented with the

name of Worker. In the same way as with the repository pattern, flama provides a base class for workers related to

SQLAlchemy tables, called SQLAlchemyWorker. In essence, the SQLAlchemyWorker provides a connection and a transaction

to the database, and instantiates all its repositories with the worker connection. In this example, our worker will only

use a single repository (namely, the UserRepository) but we could add more repositories if needed.

Our worker will be called RegisterWorker, and we can save the following code in a file called workers.py under the

src folder:

# src/workers.pyfrom flama.ddd import SQLAlchemyWorker

from src import repositories

__all__ = ["RegisterWorker"]

class RegisterWorker(SQLAlchemyWorker): user: repositories.UserRepositoryThus, if we had more repositories to work with, for instance ProductRepository and OrderRepository, we could add

them to the worker as follows:

# src/workers.pyfrom flama.ddd import SQLAlchemyWorker

from src import repositories

__all__ = ["RegisterWorker"]

class RegisterWorker(SQLAlchemyWorker): user: repositories.UserRepository product: repositories.ProductRepository order: repositories.OrderRepositoryAs simple as that, we have implemented the repository and worker patterns in our application. Now, we can move on to implement the resource methods that will provide the API endpoints needed to interact with the user data.

Resources

Resources are one of the main building blocks of a flama application. They are used to represent application resources (in the sense of RESTful resources) and to define the API endpoints that interact with them.

In our example, we will define a resource for the user, called UserResource, which will contain the methods to create,

activate, sign in, and deactivate users. Resources need to derive, at least, from the flama built-in Resource

class, although flama provides more sophisticated classes to work with such as RESTResourceand CRUDResource.

We can save the following code in a file called resources.py under the src folder:

# src/resources.pyimport hashlibimport httpimport uuid

from flama import typesfrom flama.ddd.exceptions import NotFoundErrorfrom flama.exceptions import HTTPExceptionfrom flama.http import APIResponsefrom flama.resources import Resource, resource_method

from src import models, schemas, worker

__all__ = ["AdminResource", "UserResource"]

ENCRYPTION_SALT = uuid.uuid4().hexENCRYPTION_PEPER = uuid.uuid4().hex

class Password: def __init__(self, password: str): self._password = password

def encrypt(self): return hashlib.sha512( (hashlib.sha512((self._password + ENCRYPTION_SALT).encode()).hexdigest() + ENCRYPTION_PEPER).encode() ).hexdigest()

class UserResource(Resource): name = "user" verbose_name = "User"

@resource_method("/", methods=["POST"], name="create") async def create(self, worker: worker.RegisterWorker, data: types.Schema[schemas.UserDetails]): """ tags: - User summary: User create description: Create a user responses: 200: description: User created in successfully. """ async with worker: try: await worker.user.retrieve(email=data["email"]) except NotFoundError: await worker.user.create({**data, "password": Password(data["password"]).encrypt(), "active": False})

return APIResponse(status_code=http.HTTPStatus.OK)

@resource_method("/signin/", methods=["POST"], name="signin") async def signin(self, worker: worker.RegisterWorker, data: types.Schema[schemas.UserCredentials]): """ tags: - User summary: User sign in description: Create a user responses: 200: description: User signed in successfully. 401: description: User not active. 404: description: User not found. """ async with worker: password = Password(data["password"]) try: user = await worker.user.retrieve(email=data["email"]) except NotFoundError: raise HTTPException(status_code=http.HTTPStatus.NOT_FOUND)

if user["password"] != password.encrypt(): raise HTTPException(status_code=http.HTTPStatus.UNAUTHORIZED)

if not user["active"]: raise HTTPException( status_code=http.HTTPStatus.BAD_REQUEST, detail=f"User must be activated via /user/activate/" )

return APIResponse(status_code=http.HTTPStatus.OK, schema=types.Schema[schemas.User], content=user)

@resource_method("/activate/", methods=["POST"], name="activate") async def activate(self, worker: worker.RegisterWorker, data: types.Schema[schemas.UserCredentials]): """ tags: - User summary: User activate description: Activate an existing user responses: 200: description: User activated successfully. 401: description: User activation failed due to invalid credentials. 404: description: User not found. """ async with worker: try: user = await worker.user.retrieve(email=data["email"]) except NotFoundError: raise HTTPException(status_code=http.HTTPStatus.NOT_FOUND)

if user["password"] != Password(data["password"]).encrypt(): raise HTTPException(status_code=http.HTTPStatus.UNAUTHORIZED)

if not user["active"]: await worker.user.update({**user, "active": True}, id=user["id"])

return APIResponse(status_code=http.HTTPStatus.OK)

@resource_method("/deactivate/", methods=["POST"], name="deactivate") async def deactivate(self, worker: worker.RegisterWorker, data: types.Schema[schemas.UserCredentials]): """ tags: - User summary: User deactivate description: Deactivate an existing user responses: 200: description: User deactivated successfully. 401: description: User deactivation failed due to invalid credentials. 404: description: User not found. """ async with worker: try: user = await worker.user.retrieve(email=data["email"]) except NotFoundError: raise HTTPException(status_code=http.HTTPStatus.NOT_FOUND)

if user["password"] != Password(data["password"]).encrypt(): raise HTTPException(status_code=http.HTTPStatus.UNAUTHORIZED)

if user["active"]: await worker.user.update({**user, "active": False}, id=user["id"])

return APIResponse(status_code=http.HTTPStatus.OK)Base application with DDD

Now that we have implemented the data model, the repository and worker patterns, and the resource methods, we need to modify the base application we introduced before, so that everything works as expected. We need to:

- Add the SQLAlchemy connection to the application, and this is achieved by adding the

SQLAlchemyModuleto the application constructor as a module. - Add the worker to the application, and this is achieved by adding the

RegisterWorkerto the application constructor as a component.

This will leave the app.py file as follows:

# src/app.py

from flama import Flamafrom flama.ddd import WorkerComponentfrom flama.sqlalchemy import SQLAlchemyModule

from src import resources, worker

DATABASE_URL = "sqlite+aiosqlite:///models.db"

app = Flama( title="Domain-driven API", version="1.0.0", description="Domain-driven design with Flama 🔥", docs="/docs/", modules=[SQLAlchemyModule(DATABASE_URL)], components=[WorkerComponent(worker=worker.RegisterWorker())],)

app.resources.add_resource("/user/", resources.UserResource)

@app.get("/", name="info")def info(): """ tags: - Info summary: Ping description: Returns a brief description of the API responses: 200: description: Successful ping. """ return {"title": app.schema.title, "description": app.schema.description, "public": True}It should be apparent to you already how the DDD pattern has allowed us to separate the business logic of the application (which is easily readable in the resource methods) from the data access logic (which is implemented in the repository and worker patterns). It's also worth noting how this sepration of concerns has made the code more maintainable and testable, and how the code is now more aligned with the business requirements we were given at the beginning of this example.

Running the application

Before running any command, please check that your development environment is set up correctly, and that the folder structure is as follows:

.├── README.md├── migration.py├── models.db└── src ├── __init__.py ├── __main__.py ├── app.py ├── models.py ├── repositories.py ├── resources.py ├── schemas.py └── worker.pyIf everything is set up correctly, you can run the application by executing the following command (remember to run the migration script before running the application):

> poetry run flama run --server-reload src.app:app

INFO: Will watch for changes in these directories: [...]INFO: Uvicorn running on http://127.0.0.1:8000 (Press CTRL+C to quit)INFO: Started reloader process [35369] using WatchFilesINFO: Started server process [35373]INFO: Waiting for application startup.INFO: Application startup complete.Now we can try the business logic we've just implemented. Remember, you can try this either by using a tool like curl

or Postman, or by using the auto-generated docs UI provided by flama by navigating to

http://localhost:8000/docs/ in your browser and trying the endpoints from there.

Create a user

To create a user, you can send a POST request to /user/ with the following payload:

{ "name": "John", "surname": "Doe", "email": "[email protected]", "password": "123456"}So, we can use curl to send the request as follows:

curl --request POST \ --url http://localhost:8000/user/ \ --header 'Accept: application/json' \ --header 'Content-Type: application/json' \ --data '{ "name": "John", "surname": "Doe", "email": "[email protected]", "password": "123456"}'If the request is successful, you should receive a 200 response with an empty body, and the user will be created in

the database.

Sign in

To sign in, you can send a POST request to /user/signin/ with the following payload:

{ "email": "[email protected]", "password": "123456"}So, we can use curl to send the request as follows:

curl --request POST \ --url http://localhost:8000/user/signin/ \ --header 'Accept: application/json' \ --header 'Content-Type: application/json' \ --data '{ "email": "[email protected]", "password": "123456"}'Given that the user is not active, you should receive something like the following response:

{ "status_code": 400, "detail": "User must be activated via /user/activate/", "error": "HTTPException"}We can also test what would happen if someone tries to sign in with the wrong password:

curl --request POST \ --url http://localhost:8000/user/signin/ \ --header 'Accept: application/json' \ --header 'Content-Type: application/json' \ --data '{ "email": "[email protected]", "password": "1234567" }'In this case, you should receive a 401 response with the following body:

{ "status_code": 401, "detail": "Unauthorized", "error": "HTTPException"}Finally, we should also try to sign in with a user that doesn't exist:

curl --request POST \ --url http://localhost:8000/user/signin/ \ --header 'Accept: application/json' \ --header 'Content-Type: application/json' \ --data '{ "email": "[email protected]", "password": "123456" }'In this case, you should receive a 404 response with the following body:

{ "status_code": 404, "detail": "Not Found", "error": "HTTPException"}User activation

Having explored the sign in process, we can now activate the user by sending a POST request to /user/activate/ with

the credentials of the user:

curl --request POST \ --url http://localhost:8000/user/activate/ \ --header 'Accept: application/json' \ --header 'Content-Type: application/json' \ --data '{ "email": "[email protected]", "password": "123456"}'With this request, the user should be activated, and you should receive a 200 response with an empty body.

As in the previous case, we can also test what would happen if someone tries to activate the user with the wrong password:

curl --request POST \ --url http://localhost:8000/user/activate/ \ --header 'Accept: application/json' \ --header 'Content-Type: application/json' \ --data '{ "email": "[email protected]", "password": "1234567"}'In this case, you should receive a 401 response with the following body:

{ "status_code": 401, "detail": "Unauthorized", "error": "HTTPException"}Finally, we should also try to activate a user that doesn't exist:

curl --request POST \ --url http://localhost:8000/user/activate/ \ --header 'Accept: application/json' \ --header 'Content-Type: application/json' \ --data '{ "email": "[email protected]", "password": "123456"}'In this case, you should receive a 404 response with the following body:

{ "status_code": 404, "detail": "Not Found", "error": "HTTPException"}User sign in after activation

Now that the user is activated, we can try to sign in again:

curl --request POST \ --url http://localhost:8000/user/signin/ \ --header 'Accept: application/json' \ --header 'Content-Type: application/json' \ --data '{ "email": "[email protected]", "password": "123456" }'Which, this time, should return a 200 response with the user's information:

{ "email": "[email protected]", "name": "John", "surname": "Doe", "id": "d73d4a62-dfe9-4907-91f4-f6b06f33c534", "active": true, "password": "..."}User deactivation

Finally, we can deactivate the user by sending a POST request to /user/deactivate/ with the credentials of the user:

curl --request POST \ --url http://localhost:8000/user/deactivate/ \ --header 'Accept: application/json' \ --header 'Content-Type: application/json' \ --data '{ "email": "[email protected]", "password": "123456"}'With this request, the user should be deactivated, and you should receive a 200 response with an empty body.

Conclusion

In this post we've ventured into the world of Domain-Driven Design (DDD) and how it can be implemented in a flama application. We've seen how DDD can help us to separate the business logic of the application from the data access logic, and how this separation of concerns can make the code more maintainable and testable. We've also seen how the repository and worker patterns can be implemented in a flama application, and how they can be used to encapsulate the data access logic and provide a way to group all the operations that must be performed on the data source within a single transaction. Finally, we've seen how the resource methods can be used to define the API endpoints that interact with the user data, and how the DDD pattern can be used to implement the business requirements we were given at the beginning of this example.

Although the sign-in process we've described here is not entirely realistic, you could combine the material of this and a previous post on JWT authentication to implement a more realistic process, in which the sign-in ends up returning a JWT token. If you're interested in this, you can check out the post on JWT authentication with flama.

We hope you've found this post useful, and that you're now ready to implement DDD in your own flama applications. If you have any questions or comments, feel free to reach out to us. We're always happy to help!

Stay tuned for more posts on flama and other exciting topics in the world of AI and software development. Until next time!

Support our work

If you like what we do, there is a free and easy way to support our work. Gifts us a ⭐ at Flama.

GitHub ⭐'s mean a world to us, and give us the sweetest fuel to keep working on it to help others on its journey to build robust Machine Learning APIs.

You can also follow us on 𝕏, where we share our latest news and updates, besides interesting threads on AI, software development, and much more.

References

About the authors

- Vortico: We're specialised in software development to help businesses enhance and expand their AI and technology capabilities.